This week’s National Symphony program features Paul Hindemith’s beautiful When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d: A Requiem for those we love in a program conducted by Christoph Eschenbach. This was one of the favorite works of Robert Shaw, who commissioned Hindemith’s remarkable setting of Walt Whitman’s eulogy for Lincoln. Here’s the essay I wrote for the NSO program (which opens with Joshua Bell in the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto — hence the lede):

A descendant of one of Mendelssohn’s cousins, Arnold Mendelssohn, turned out to be the first composition teacher of another precociously gifted musician, Paul Hindemith (1895-1963), who was born in Hanau (near Goethe’s city of Frankfurt). Hindemith came of age during a period of violent, revolutionary change in the early 20th century – the years that gave birth to modernism in its many forms. In the 1920s, Hindemith caused one scandal after another with his stage works and was considered a rebellious upstart who flirted with the avant-garde.

Like Shostakovich vis-à-vis Stalin, Hindemith managed to incur the personal displeasure of Hitler. The latter’s unyielding loathing of Hindemith was set in stone after seeing a scene from the satirical 1929 opera Neues vom Tage (“News of the Day”) featuring a “nude” soprano (actually, in a flesh-colored stocking) as she sings in the bathtub. Though he wasn’t Jewish, Hindemith gained a place of honor among the “degenerates” singled out by leading Nazis, who regarded him as “spiritually non-Aryan” and banned his music. The situation was actually more convoluted, however, with some pro-Hindemith voices among the hierarchy.

Hindemith may have hoped to influence cultural policy by finding a way to remain in Germany – in hindsight, his failure to express vociferous dissent from within the Third Reich has been criticized – but the situation grew intolerable and Hindemith, together with his wife (who was partially Jewish), emigrated first to Switzerland and then to the United States, where he influenced a new generation during his 13-year tenure teaching at Yale. When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d ranks as the most significant creative legacy of this American period – Hindemith and his wife became U.S. citizens in 1946, the year of its premiere, although they returned to Europe in 1953 – and was acclaimed “a work of genius” by the legendary critic Paul Hume, writing of a performance at the National Cathedral in 1960.

“It is probable,” the great conductor Robert Shaw once declared, “that no foreign-born composer has made such a direct and healthy contribution to American music as Paul Hindemith.” Shaw was in fact the prime mover behind When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d, which he commissioned for what was then known as his Collegiate Chorale in the winter of 1945. Shaw led the world premiere in New York on May 14, 1946 (featuring a young George London as the male soloist), and he championed the work for the rest of his career; according to Michael Steinberg, Shaw treasured Hindemith’s dedication of the score to him “as perhaps the most significant honor of his professional life.”

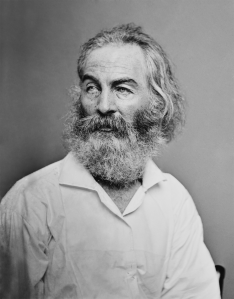

The immediate occasion that prompted Lilacs was the sudden death in office of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in April 1945 – 80 years after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln had plunged the nation into a period of prolonged mourning and soul-searching, the artistic fruit of which was one of Walt Whitman’s (1819-1892) most extraordinary poems. Hindemith had actually begun to cultivate a fascination with Whitman’s poetry long before: as far back as 1919 he had composed three “hymns from Whitman” (for baritone and piano, in German), including a setting of “Sing on, there in the swamp” (the fifth vocal section in Lilacs).

In his book New World Symphonies, Jack Sullivan reports that “Shaw initially took this single song to Hindemith, who had reworked it in 1943, with the proposal that it be used as a memorial to Roosevelt. Hindemith’s admiration for both President and poet was so great, however, that he responded, ‘No, we should do the whole thing.’ A two-minute song became an hour-long New World Requiem, an American epic set to European forms, including a sinfonia, a chorale, marches with trios, double fugues, arias, choruses, motets, fanfares, and much else.”

To undertake “the whole thing” entailed setting a text of 208 lines comprising more than 2200 words, arranged by the poet in 20 sections. In one of his commentaries, Robert Shaw refers to the “technical virtuosity” of setting such a lengthy text meaningfully within a musical span lasting about an hour (without, that is, resorting to “dry recitative”). He contrasts the first 20 minutes of Bach’s B minor Mass, which sets just three words, with the roughly 900 words Hindemith sets in the first 20 minutes of his work: “And these are words not lightly tossed into the composition heap. They are Walt Whitman words, burdened with emotional ponderosity and ponderability.”

By 1865, Whitman had already gathered a collection of poems inspired by his experiences nursing the wounded and dying in Washington, D.C., which he titled Drum-Taps (an excerpt from which can be seen engraved at the Q St. entrance to the DuPont Circle Metro station). Within weeks of Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theater on Good Friday in 1865, Whitman had completed a new addition to this, When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d (a “dooryard” refers to a yard adjacent to the door of a house). That poem was published in the Sequel to Drum-Taps by the D.C.-based Gibson Brothers.

Whitman weaves a complex network of imagery together to fashion the deeply moving reflections of his Lincoln elegy. He mines the evocative power of three dominant symbols, which recur but with ever-changing connotations throughout the poem: lilacs, the “Western star” (i.e., Venus), and the “gray-brown” wood thrush. The specific occasion of Lincoln’s death (the President is never referred to by name) and the spectacle of “the silent sea of faces” grieving as the coffin passes give way to further meditations on the cycle of mourning and the artist’s task. Whitman builds to a larger vision of loss and life’s journey, drawing on images from nature and American civilization alike. The poem reaches a climax with its epiphany of the “death carol” and compassion for the war dead, ending with an affirmation of “retrievements out of the night” and the work of memory.

When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d moreover incorporates much musical imagery (above all, references to “song”). Not surprisingly, it has appealed to a remarkable variety of composers, including Roger Sessions, George Crumb, George Walker (whose Lilacs won the Pulitzer Prize in 1996 and whose recent composition will be featured later this season in an NSO premiere), and, most recently, Jennifer Higdon. For his setting, Hindemith translates Whitman’s poetic elegy into a kind of combined oratorio-requiem, with the subtitle A Requiem “For Those We Love.”

Hindemith always maintained a deep and also practical respect for musical tradition, despite his earlier reputation as a shocker (which by this time, in any case, had long since been overwritten by his image as an éminence grise). His emphasis on pragmatism might be seen as one manifestation of a general cultural rejection of Romanticism – including the cult of art for art’s sake and the idealized notion that musical inspiration should not be sullied by the contingencies of everyday reality. And Hindemith was also hearkening back to a pre-Romantic ethic of music as a craft to be plied. He had an affinity for Baroque counterpoint and other technical tricks of the trade, all of which are in evidence in the score of Lilacs (including his profound admiration of J.S. Bach).

Implicit in his division into arias, duets, choruses, arioso, and the like are references to Bach’s Passions. Aficionados of the St. Matthew Passion will recognize echoes in his use of particular instrumental timbres, meters, and even emotional pacing. And another, later model is also evident: Brahms’s A German Requiem, with its male and female soloists and symphonic use of orchestra. The Kurt Weill expert Kim Kowalke has pointed out that Hindemith originally considered using An American Requiem as his subtitle, thus drawing attention to the parallels with Brahms in a way that “seems to mirror the composer’s ambivalence about his own national identity at this crucial point in his career.”

Yet a further layer is encoded by the phrase Hindemith did choose: A Requiem “For Those We Love.” Kowalke’s research led to the discovery that the instrumental hymn that occurs in section 8 (a quotation of an Episcopal hymn in which that phrase occurs) was known to the composer to be based on a Jewish liturgical melody, thus conferring what musicologist Richard Taruskin describes as “a specifically post-Holocaust resonance.” Together, writes Philip Coleman-Hull, the music and the poetry of Hindemith’s Requiem “intertwine in a reciprocal relationship, so that the ‘Americanness’ of Whitman’s poetry infuses Hindemith’s musical response, and the music, in turn, illuminates Whitman’s text.”

That illumination of the pre-existing text indeed involves a good number of European imports – including the massive double fugue (i.e., fugue based on two different themes) in which section 7 culminates. Robert Shaw, in conjunction with his mentor, Julius Herford, incisively parsed the 11 sections into which Hindemith divides his Lilacs into a larger architectural scheme of four movements as follows. The purely instrumental Prelude establishes the fundamental key of C-sharp minor – first in the bass, against which the pregnant motif A-C-F-E is heard (each of whose notes defines key tonality governing the larger structures to follow). The first movement extends through section 3, ending with the choral march and a canon between solo baritone and orchestra.

Sections 4-7 comprise the second movement in Shaw’s analysis, in which Whitman’s poem depicts “the stage of receiving knowledge, the first understanding.” Hindemith’s tonal scheme shifts to A minor and culminates in the E minor/major double fugue. There is a darkening in the C minor beginning the third movement (sections 8-9) as the poet “moves from the state of receiving knowledge, with its shock and its ecstasy of tribute, to the state of possessing knowledge.” Following the duet between mezzo, who is closely associated with the bird’s voice, and the baritone, the Death Carol (in F minor) ends with a passacaglia at “Approach, strong deliveress.”

There follows “the panorama of death” in the fourth movement (sections 10-11), with the baritone evoking a terrifying vision of war. Hindemith’s counterpoint channels something of the restless, sardonic energy of a march Weimar era-style, while an off-stage bugle quotes Taps. The baritone also initiates the finale of Lilacs (section 11), where Whitman and Hindemith join hands to stage a sense of reconciliation, gathering together the poem’s principal symbols in the final chorus. In his one emendation to the poem, Hindemith has the soloists intone the opening line once again in a subdued monotone. The reiteration of the fundamental C-sharp minor underscores the convergence of journey and cycle.

The quietness of the ending makes perfect emotional sense for Shaw, who sums up Hindemith’s Lilacs as “a hymn for those he loved. It has nothing to do with proclamations of national mourning, the public beating of breasts, but with quiet private grief and a lonely broken heart.”

(c) 2014 Thomas May. All rights reserved.

Filed under: American literature, poetry, program notes, requiem