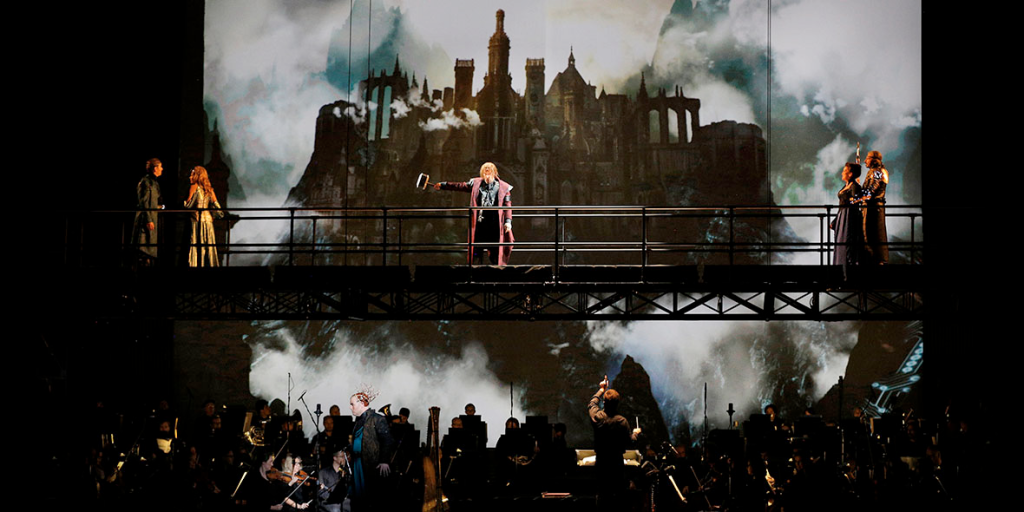

Richard Paul Fink (Alberich) and Daniel Sumegi (Hagen); photo ©Alan Alabastro

Talk about a buildup: I can’t think of any other work of art, let alone opera, that stokes our sense of anticipation with such prolonged intensity as the Ring’s grand finale. The whole shebang came about, after all, because Wagner wanted to fortify the emotional payoff of what became Götterdämmerung.

Providing the back stories leading up to his depiction of Siegfried’s downfall and Brünnhilde’s final enlightenment isn’t the only thing the first three Ring operas are supposed to do. They’re meant to give these events a dramatic and musical weight that’s only possible if the audience is persuaded to commit itself over the Ring’s vast scale. And that’s what ultimately can make the cycle feel so “cosmic” – not its mythic congeries of mermaids, gods, giants, dwarves, et al.

On Friday night Seattle Opera arrived at the conclusion of its signature Ring – the first of three cycles being given in this Wagner bicentennial year, as well as in the final season of general director Speight Jenkins’ long tenure.

Which is to say, there’s an additional layer of significance to this Ring for Seattle audiences and for the impressive percentage of non-local fans who’ve made the pilgrimage from afar for what may be their last chance to see this production.

I’ve found this round of the Seattle Ring immensely satisfying as a whole. For those who have had the fortune to see earlier iterations since it was unveiled in 2001, this latest encounter delivers a special cumulative effect of its own by way of comparison with the previous versions. An important factor here is the readjustment of the chemistry of the performing forces, with both a conductor and key members of the cast new to the production.

Die Walküre: Alwyn Mellor (Brünnhilde), Greer Grimsley (Wotan); photo ©Elise Bakketun

One of these is the British soprano Alwyn Mellor, whose portrayal of Brünnhilde in Die Walküre had the dramatic range to match her enthralling vocal presence. It’s been said that the Ring contains three Brünnhildes, but already in this opera Mellor homed in on different layers of her character beyond the exuberant war cry that first introduces her – above all in the Death Annunciation scene, where she learns compassion from the doomed Wälsung twins, but also in the bewilderment displayed in her last confrontation with Wotan. More than ever before, I was riveted by the “gulf of misunderstanding” that tragically separates her from the “warfather” god – but that will set her on the path to her own liberation.

Unfortunately Mellor fell prey to an ailment and had to bow out of the rest of the cycle. If Lori Phillips, the cover for Brünnhilde, saved the night with her passionate and well-acted performance in Siegfried’s final scene, her ability to step in the spotlight at the last-minute for the brutal demands of Götterdämmerung was little short of miraculous. Both the “continuation” of her love duet on the rock with Siegfried and Brünnhilde’s scene with Waltraute were highlights of the evening. Given the circumstances, it’s hard to fault Phillips for being less convincing in her character’s volatile transformation in the second act. There was a further loss of emotional complexity in the Immolation Scene, where the toll on her upper range became most apparent.

Götterdämmerung: Stefan Vinke (Siegfried), Daniel Sumegi (Hagen), and Markus Brück (Gunther); photo ©Alan Alabastro

I suspect this sudden change in the partner he had rehearsed with most closely may account, in part at least, for a less satisfying rendition of the mature Siegfried by the German tenor Stefan Winke (also new to the production) than the young hero he had managed to make so compelling two nights before.

But another part of the “Siegfried problem” is beyond any individual performer’s control. Let’s face it: Wagner’s actual presentation of Siegfried in Götterdämmerung is deeply flawed. No sooner does Brünnhilde send him off to perform great “new deeds” than he is duped by Hagen and the scheming Gibichungs. He’s not only passive but (rather like Wotan) perfectly willing to compromise himself morally – and this on his own accord – to get what he wants (Gutrune); and like Mime, he fails to learn what he needs to know when he has the chance to from the Rhinedaughters.

Stefan Vinke in Siegfried’s “Forging Song”

At any rate, Vinke’s singing still produced thrills (including a daringly sustained high C in his response to the hunting party soon before his death). But apart from his eerily shaded voice as he sang from within a cave to Gunther’s onstage lip-syncing for the abduction of Brünnhilde, there was far less variety of phrasing than Wednesday night; Vinke tended toward a more one-size-fits-all projection and, most problematically for me, failed to convey the sense of Siegfried’s sudden, harrowing realization of what has been lost in his final, “undrugged” recall of Brünnhilde before he dies.

Still, the massive prelude-plus-first act (nearly comparable in length to the whole of Rheingold) was among the most memorable segments of the cycle. It almost seemed to play out in one sustained arc of thoroughly riveting theater.

Götterdämmerung: Alwyn Mellor (Brünnhilde) and Stephanie Blythe (Waltraute); photo ©Alan Alabastro

Stephanie Blythe’s contributions to the Seattle Ring are pretty much exaggeration-proof. As Fricka in the first two operas, her complex but loving relationship with the excellent Greer Grimsley’s Wotan have been a defining feature of director Stephen Wadsworth’s interpretation since it premiered. As if that weren’t enough, her sculptural phrasing and vocal phrasing also added texture and atmosphere to the Norns (joined by Luretta Bybee and Margaret Jane Wray, who delivered such a moving Sieglinde). And Blythe’s Waltraute, with its “preview” of the Immolation Scene summing-up, actually eclipsed the latter on this occasion. Particularly in this staging, it is this scene that represents the point of no return (rather than the Rhinedaughters’ last-ditch plea later in act three).

I was also extremely pleased with newcomer Wendy Bryn Harmer. She’d also appeared as one of the Valkyries and as a distraught Freia (a great addition to the roster of gods, as was the demigod partially responsible for her plight, Loge, given a mesmerizing performance by Mark Schowalter). Her Gutrune for once had some depth rather than being a mere pawn – uncannily reminiscent of Sieglinde as the victim of a hostile men’s world, but also pathetically desperate at her chance for love, even if it’s cheating, with Siegfried. But to my taste, fellow Seattle Ring newbie Markus Brück remained too constrained by the passivity of his character as the ineffectual Gibichung ruler Gunther.

Götterdämmerung: Daniel Sumegi (Hagen) and the Vassals; photo ©Elise Bakketun

Making up for this – and grounding a sense of the “real world” power struggle into which Siegfried blithely blunders – was Daniel Sumegi’s Hagen, in a portrayal of spine-chilling menace and cold-blooded calculation. So weighty is the evil this Hagen incubates (manifested with peals of darkly rolling vocal thunder) that even he appears troubled by its implications, as we see in another highly successful scene: the dream-encounter with Alberich. As one of the leading exponents of the latter singing today, Richard Paul Fink has been intensifying his spiteful phrasing and physical acting to such a point that you worry a little he won’t be able to snap out of character.

Yet after this scene and the superb first act, I did feel a kind of dwindling, anti-climactic effect, above all in the conclusion of the cycle. The visual staging of the post-Immolation cataclysm – is there a more impossible design challenge in the theater? – has at least arrived at a reasonably effective compromise (which, for the sake of those still intending to see it, I won’t give away here).

I’ve decided this sense of anti-climax results from a mix of the Ring’s inherent weaknesses which Wagner was never able to sort out and specific choices of this production, compounded with things being thrown off balance owing to the last-minute unavailability of Mellor’s Brünnhilde.

Das Rheingold Markus Brück (Donner), Andrea Silvestrelli (Fasolt), Wendy Bryn Harmer (Freia), Greer Grimsley (Wotan), Stephanie Blythe (Fricka), Ric Furman (Froh), and Mark Schowalter (Loge); photo (c)Elise Bakketun

While the scenically realistic, Pacific Northwest-inspired look of the fabulous sets designed by Thomas Lynch is largely responsible for the moniker “green” Ring, Seattle Opera’s production isn’t really about imposing some sort of environmental concept. But those who refer to it as a “traditional” Ring are sorely mistaken. This notion has been kicking around because of the tastefully archaic aura of the late Martin Pakledinaz’s costumes or perhaps because of the plausibly mythical zone in which everything plays out (as opposed to, say, the rundown motel on Route 66 for Rheingold in the much-scorned new Bayreuth Ring directed by Frank Castorf).

Das Rheingold: Jennifer Zetlan (Woglinde), Cecelia Hall (Wellgunde),Renée Tatum (Flosshilde), Richard Paul Fink (Alberich); photo (c)Elise Bakketun

Yet Seattle Opera’s Ring, too, is strongly rooted in a vivid directorial concept. The brilliance of director Stephen Wadsworth’s vision, which centers around an almost Chekhovian psychological realism, is that he has evolved this both from a deep knowledge of Wagner’s text (the combine of words and music, that is) and from obsessively detailed, prolonged rehearsals with the cast to ensure an organically coherent portrayal of the characters and their interactions.

Thus, as mentioned, there’s genuine love between Wotan and Fricka, which underscores the sense of personal tragedy in the god’s dilemma in Die Walküre and its fallout. This does of course mean giving precedence to some elements in the Wagnerian text and overlooking others (such as Wotan’s harsher persona as “war father”). It also means inserting things into the text that aren’t there in the first place so as to draw out an implication: we see Fricka suddenly appear for the hyperintense conclusion to act two of Die Walküre to greet Hunding, only to be dumbstruck when Wotan slays him (an effective and justifiable choice, I thought, to make us think of the future she, too, has to face; otherwise she simply disappears from the cycle after her earlier confrontation).

Die Walküre: Stephanie Blythe (Fricka), Greer Grimsley (Wotan); photo (c)Elise Bakketun

Wadsworth’s essential approach is to humanize Wagner’s mythical characters and their behavior. This perspective pays its richest dividends in Die Walküre and Siegfried, which, for me, are the two most impressive successes of the Seattle Ring. In fact, often though we’re told that the Ring is a vast epic containing the history of the world, a significant proportion of the cycle (the middle two operas, more or less) actually centers around scenes of intimate dramatic communication between two characters. Wadsworth’s style and concept are ideally suited to these. His humanizing also touch goes a long way toward animating the expository stretches of Das Rheingold, with its much larger ensemble.

Stephen Wadsworth in rehearsal

The Achilles heel seems to be in the crowd scenes of Götterdämmerung and in the old-fashioned, grand opera style “Lohengrinizing” (as G.B Shaw called it) that makes these parts of the last Ring opera sometimes seem such a throwback. There’s a lot of rustling about from the chorus of Vassals in the second act in response to Hagen’s summoning (where, musically, Wagner seems to nod), but it doesn’t convey the accumulation of menacing tension, the sense of a whole society on the verge of collapse despite the distractions of wedding celebration.

A similar situation lessens the impact of the third act. A comic turn in the Rhinedaughters’ reappearance at the top of the act which has them horsing around is presumably meant for relief, but that choice has always struck the wrong note for me. Wadsworth’s forte is evoking the intimate and personal, but the atmosphere of apocalypse remains absent in the scene of Siegfried’s murder and in the final scene. And it’s a problem that goes beyond this particular production, affecting many others. Wagner himself acknowledged the challenge when he suggested that all the knots are really worked out in what the final music tells us.

Maestro Asher Fisch

As the production’s new conductor, Asher Fisch (for whom Daniel Barenboim was an important mentor), proved to be a key asset in making this latest edition – neatly fine-tuned by Wadsworth in increasingly subtle ways – the most successful run since the premiere of Seattle’s Ring production in 2001. Fisch coaxed the most ear-catching collections of sounds and color from this orchestra that I’ve ever heard in their Ring playing.

There was some unevenness, to be sure: Siegfried’s Funeral March sounded inexplicably hollow, and moment after glorious moment of the final scene was thrown away, like an actor so afraid he’ll forget the words of a great Shakespeare monologue he rattles them off without trying to create an interpretation.

Overall, what Fisch sacrificed in sheer dramatic tension (not to mention Soltiesque playing to the gallery) through his often measured tempo choices was compensated by the continual unfolding of layers of the score that often lie buried. The woodwind writing in the last scene of Die Walküre, for instance, bloomed with breathtaking beauty, while Siegfried’s second act was shot through with almost psychedelic streaks of color – growling low brass and electrifying string figurations.

And for the most part Fisch succeeded in integrating the singers into the total fabric of sound and in contouring the ensemble to the dramatic dimension. (One strange quirk of Wadsworth’s stage direction, which posits the characters often “hearing” the music from the orchestra, has them react in stylized, silent-film-type gestures to musical accents.) The result made an incalculable contribution to the gathering theatrical effectiveness of the cycle as each evening progressed.

At the conclusion of this first of three cycles to be performed in August, Speight Jenkins briefly addressed the audience, calling attention to the incredible efforts of everyone involved in what he termed “the biggest collaboration there is in all art.” And he pointed out that this is the valedictory Ring under his long tenure with the company, which has been defined by its Ring productions. It’s hard to imagine a more moving or memorable way to leave the stage.

–Thomas May

Filed under: opera, review, Ring cycle, Seattle Opera, Wagner