Saimir Pirgu (Alfredo) and Nicole Cabell (Violetta). ©Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

(San Francisco Opera’s revival of La Traviata has just opened. Following is the full version of the essay I wrote for SFO’s program book.)

On New Year’s Day of 1853 — more than two weeks before the opening of Il Trovatore — Giuseppe Verdi wrote to one of his businessmen-friends about the challenges of finding suitable libretti: “I want subjects that are new, great, beautiful, varied, daring … and daring to an extreme degree, with new forms, etc., and at the same time [that are] capable of being set to music.”

The thirty-nine-year-old composer goes on to mention his latest project, a new opera for La Fenice in Venice. Based on La Dame aux Camélias, the recent stage sensation by Alexandre Dumas the Younger, Verdi writes, “[it] will probably be called La Traviata. A subject for our own age. Another composer would perhaps not have done it because of the costumes, the period, or a thousand other foolish scruples, but I did it with great pleasure. Everyone complained when I proposed putting a hunchback on the stage. Well, I wrote Rigoletto with great pleasure. The same with Macbeth.”

Even set against his bold treatments of Victor Hugo and Shakespeare, Verdi was fully aware that he was taking an unusual risk by adapting such contemporary material for the opera stage. It was one thing to lace his operas with political themes “topical” for Risorgimento Italy, but something else altogether to address contemporary sexual mores and issues of social class not as light-hearted comedy but as full-on tragedy.

Still, for us today, it’s admittedly hard to think of La Traviata as controversial. This nineteenth work in Verdi’s oeuvre is not just a box office guarantee, but for many the very definition of opera.

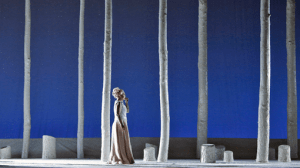

La Traviata: 2014 production at San Francisco Opera; ©Cory Weaver/SFO

Over the past five years La Traviata has securely held its position as the opera most frequently performed around the world: Violetta even surpasses her fellow tubercular Parisian, La Bohème’s Mimì, as far as this measurement of popularity goes. Popular culture is replete with variations on both stories: for the (once) hip Bohemians of Rent there are the hallucinogenic colors and all-star remake of “Lady Marmalade” of Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge!

La Traviata was the opera chosen to launch the past season at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, marking Verdi’s bicentennial year. Any controversy that is generated comes from interpretive decisions: Dmitri Tcherniakov’s new production at La Scala, rather tamely set in the present, was theatrically booed by the loggionisti.

(Without doubt this was a reaction more vociferously negative than the fabled “fiasco” of the world premiere on March 6, 1853, which really came down to a mostly tepid response. Verdi himself stoked the legend of a disastrous opening-night reception, and the next staging a year later, also in Venice and with a slightly altered score, became an indisputable success.)

Nicole Cabell (Violetta) and Saimir Pirgu (Alfredo). ©Cory Weaver/SFO

The irony of this is rich, because with La Traviata Verdi intended for the first time to have an opera staged with contemporary dress, though in the event he was compelled to accede to the Venetian censor’s demand to shift the period back to “circa 1700” as a comfortably safe temporal buffer. (The censorship situation there, it should be noted, was considerably more liberal than that found in other leading Italian theaters; it was for the same house in Venice that Verdi had written Rigoletto two years before.)

In later revivals Verdi acquiesced to this historical distancing. As a consequence, by the time operagoers finally encountered stagings of Verdi’s original vision of a work that would actually be set in the era in which it was composed, La Traviata had already become a “period piece.”

One of the chief arguments against directorial updatings — that they betray the composer’s original “intentions” — would have to take into account this sort of compromise constantly imposed on Verdi in order to get the subjects he chose to set to music produced. (Even the title — usually translated “The Fallen Woman,” though more literally it means “The Woman Who Went Astray” — documents a compromise for the title Verdi originally wanted: Amore e Morte.)

But the issue of Traviata’s temporal setting represents the mere surface. The great Verdi expert Julian Budden rightly points out that the lofty language indulged in by Verdi’s ever-compliant, ever-bullied librettist for the project, Francesco Maria Piave (recently responsible for adapting a Victor Hugo to the libretto of Rigoletto) at times ventures far from Dumas, giving an overall impression that is old-fashioned and “strictly operatic.” As a result, “even if [Verdi] had had his way in 1853 the modern setting would have seemed purely metaphorical.”

Instead, the bold modernity of La Traviata — the sense that this is “a subject for our own age” — has to do with the challenges Verdi set himself to grapple with a new kind of psychological realism: a realism of intimate, internal emotions as opposed to the grand passions that burn in Traviata’s swashbuckling immediate predecessor, Il Trovatore.

At one point Verdi was in fact working on both operas concurrently, and the most identifiably Trovatore-like moments in the score of Traviata are precisely those in which Verdi adheres most obviously to the conventional forms of the cabaletta (the “flashy,” usually faster-paced final section of a lengthy aria or duet).

Traviata‘s psychological realism was prompted by the subject matter of high-class prostitution and intimate relationships projected against the screen of modern urban life, with its ugly realities and fears, in particular those of poverty, alienation, and disease. In La Traviata Verdi turns to the raw facts of everyday life as experienced by people we can recognize (however costumed or wigged).

Nicole Cabell (Violetta). ©Cory Weaver/SFO

If we consider the realm of visual arts, the revolution represented by Édouard Manet in this regard still lies ahead: in 1863 he caused consternation by representing prostitution in Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, which he followed later that year with the even more-controversial Olympia, updating the idealized and mythological image of Venus into a present-day courtesan.

Not until a pair of works that premiered in 1816 (both produced in Naples) — already within Verdi’s lifetime—did Italian opera even begin to represent death onstage for the first time: the long-lived Michele Carafa’s Gabriella di Vergy and Otello (when permitted by the censors) by his contemporary Gioachino Rossini.

And the terrifying details of death by tuberculosis had no operatic precedent. (The ill-fated Antonia from Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann and both Leoncavallo’s and Puccini’s takes on La Bohème were still decades in the future.) “Poetic” dementia of the Lucia-di-Lammermoor brand is a far cry from the pathology of Violetta’s deathbed scene.

Our very first glimpse of the heroine onstage, in fact, specifies that she is consulting with Doctor Grenvil in the middle of her party. For a more-pertinent perspective on the contemporary and moral relevance of the situation depicted by Dumas and Verdi — in contrast to the tropes of Romantic individualism already established by Victor Hugo, even if his plays defied the censors — it might be useful to think of the original impact of plays like The Normal Heart and Angels in America in daring to channel the emotions caused by the AIDS crisis for the stage.

In The Literary Lorgnette, her study of the links between opera and literature in nineteenth-century Russia, Julie A. Buckler explores La Traviata’s legacy to the East, from the time it was first presented during the week of coronation festivities for Tsar Alexander II in 1856.

The opera, observes Buckler, “occupied a problematic social and aesthetic middle ground for Russian critics, depicting the demimonde [the term Dumas himself coined for the openly “secret life” of high-class sex workers] with an unnerving blend of Romantic and Realist convention.”

A new production by a Russian troupe in 1868 prompted an indignant review from the composer and critic Alexander Serov. Buckler quotes his objections to the “hospital-like” effect of the deathbed scene in particular. Serov fretted that in the future operas will be written in which “we will be taken, probably, into a clinic and made to be witnesses of amputations or the dissection of corpses!”

Nicole Cabell (Violetta). ©Cory Weaver/SFO

This fear of the opera’s corporeality and representation of disease, as Buckler points out, is inevitably linked with anxiety about its representation of sexuality. In his first private encounter with Violetta, Alfredo warns that her lifestyle is killing her, that she needs to take better care of her health — and, surely enough, she begins to convalesce during their idyll in the country, far from the sensual stimulation of Paris. Violetta’s situation fuses the three major themes of sex, sickness, and money.

Susan Sontag handily characterizes this fusion in her influential Illness as Metaphor, emphasizing the connotations shared by frivolous spending (with its implications of sexual promiscuity) and “consumption,” the word commonly used for tuberculosis: “Early capitalism assumes the necessity of regulated spending, saving, accounting, discipline—an economy that depends on the rational limitation of desire. TB is described in images that sum up the negative behavior of nineteenth-century homo economicus: consumption; wasting; squandering of vitality.”

Much has been made of the immediate enthusiasm with which Verdi reacted to seeing Dumas’ play while he was staying in Paris in 1852, soon after it opened. Despite the pressures of getting Trovatore produced, Verdi simultaneously completed his score for Traviata at record speed. Of course it is an inherently dangerous prospect to attempt to tease out connections between an artist’s personal life and an autonomous work of art.

Alexandre Dumas, fils

Budden belabors that point by ridiculing the commonplace assumption that Verdi responded so strongly to Violetta’s story because, by this time, he was cohabiting with Giuseppina Strepponi, a former singer (she created the role of Abigaille in Nabucco) regarded by the provincials in Busseto, where he lived, as a woman of “loose virtue” on account of her illegitimate children from previous affairs.

Yet Verdi hardly need have fictionalized Giuseppina as Violetta to be attracted to the themes involved in La Dame aux Camélia — and to the larger archetype of real or perceived “fallen women” he created in six operas between 1849 and 1853, as examined by the late Joseph Kerman in his essay “Verdi and the Undoing of Women.” These women, who “are condemned for their sexuality” and as a result “suffer or die,” “may have allowed the composer a way to reflect on the social and private implications of his affair.”

Writes Kerman: “Of course Verdi would never have dreamt of equating Strepponi with Violetta. The point is that Violetta allowed him to explore feelings of love, guilt, and suffering that he learned from his experience as Strepponi’s lover. Verdi explored similar feelings in other operas around the same time,” though Kerman adds that “the fallen woman syndrome retreats” from his work after Traviata as new concerns come to the foreground.

Nicole Cabell (Violetta) and Vladimir Stoyanov (Germont). ©Cory Weaver/SFO

The adultery represented in Stiffelio, the opera he wrote just before the experimental breakthrough of Rigoletto, in some ways can even be seen as a trial run for Traviata with its near-contemporary (early nineteenth-century) setting and focus on conflicting bourgeois values.

The source material for La Traviata — the play by Dumas, in turn adapted from his very first literary success, a novel published in 1848 — itself stands in a complicated relationship to the “raw data” of the author’s experience, even if some degree of both the novel’s and the play’s popularity involved the titillating glimpses they afforded “behind the scenes” into the illicit liaisons of well-to-do Parisian society.

Dumas’s novel, never out of print and recently published in a delightfully fresh new translation by Liesl Schillinger, includes nitty-gritty details about money and the day-to-day life of a high-class prostitute.

Naming his heroine Marguerite Gauthier, Dumas famously drew on his real-life affair with the already legendary courtesan Marie Duplessis but has long been castigated by feminists — as has La Traviata, to be sure — for co-opting a woman’s experience, distorting Marie Duplessis’s own autonomy through the filter of male desire and creating a hybrid “Madonna–whore” to fulfill the full spectrum of that desire. (Ironically, Dumas has been credited with coining the word “feminist” in a later pamphlet from 1872, L’Homme-Femme.)

In her recent biography of Duplessis, The Girl Who Loved Camellias, Julie Kavanagh traces the differences between the cultural icon of literature, stage, and screen and the real person who fled an abusive father and her native Normandy, arriving in Paris at the age of thirteen and transforming herself from an impoverished waif into an independent and sophisticated woman “determined to profit from Parisian culture and sample the same hedonistic pleasures available to men.”

But the treatment of Duplessis by Dumas was in its own way multifaceted, remarks Kavanagh. The novel was “part social document, part melodrama, both ahead of its time and rigidly conventional,” while the play remained an object of admiration by no less than Henry James. She quotes the latter’s verdict: “[Dumas] could see the end of one era and the beginning of another and join hands luxuriously with each.”

And what about Verdi’s treatment of the character originally inspired by Duplessis? Kavanagh finds that both Dumas and Verdi “softened her, capitulating to the romantic ideal that sought to exonerate and desexualize the fallen woman.” In Verdi’s opera, the “sordid” details of Violetta’s profession are essentially erased, her disease filling its place. She is in fact “etherealized”: “Un dì, felice, eterea” (“One day you appeared before me, happy, ethereal”) sings Alfredo in his early confession of love.

Indeed, the very first music Verdi gives us, in the Prelude — a musical portrait of Violetta — is a kind of sonic dematerialization. Divided violins suggest a sickly halo for this suffering saint. The faint similarity to Wagner’s “spiritual” string sound in the Prelude to Lohengrin (premiered in 1850, though not produced in Italy until 1871) only underscores the divergent aesthetics: increasingly, Wagner would turn to legend and myth as the vehicle for psychological truth, whereas here, for Verdi, the life we find around us serves that purpose.

Nicole Cabell (Violetta). ©Cory Weaver/SFO

The Prelude as a whole captures the heroine’s ambiguity: a woman who has sacrificed for love but who has also been defined by her devotion to pleasure. Despite having to shift the period of the action, Verdi incorporates an unmistakable sense of place — of the modern city par excellence, Paris, an epicenter of pleasure — through the endlessly dancing gestures of his music.

Waltz time is the identifiable signature of La Traviata, essential to its unique tinta; later, in the third-act prelude, the “halo” music is supplemented by a haunting melody breathing the melodic spirit of Chopin.

Why has La Traviata remained so enduringly contemporary for all its Romantic sublimation of the characters’ sexuality? If the plot shows Violetta being victimized, “redeemed” by her sacrifice, it is ultimately the music Verdi imagined that mediates our experience of these events. As Kerman eloquently notes: “Music traces the response of the characters to the action — and operas, like plays, are not essentially about the vicissitudes of women (or men); operas are about their responses to those vicissitudes.”

Take, above all, the remarkable duet between Violetta and Giorgio Germont that is the hinge of the opera—a duet far more involved in its musical design and emotional range than the two we get in the outer acts for the pair of lovers. We might be chagrined by Violetta’s willingness to accede to the senior Germont’s demands, but the music lays bare the psychological intensity both characters experience at each stage of the argument.

Vladimir Stoyanov (Germont). ©Cory Weaver

The achievement is comparable in its way to the pivotal duet between Wotan and Fricka at the heart of Wagner’s Ring, though Germont emerges as more psychologically complex. “Germont is not the monster of patriarchal authority that he is in the play,” Kerman writes. “Music recasts him as a fellow human being who moves her by his own unhappiness.”

Overall, Verdi still found it necessary at this point in his career to balance the expectations represented by the conventional formalities of Italian opera with the unique musical needs of a particular dramatic situation.

That explains how La Traviata can seem to look ahead, particularly in its novelty of material and psychological acumen, while adhering to the mold of the Italian operatic tradition Verdi had inherited — though beautifully pared down and simplified to their essence for this admirably economical score.

Saimir Pirgu (Alfredo) and Nicole Cabell (Violetta). ©Cory Weaver/SFO

In their recent A History of Opera, Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker draw attention to this paradox, noting that “this outward conformity” to musical tradition disguises two key ways in which the opera “breaks new ground.” One is the series of musical cues — above all the waltz, with its implications of “social velocity and uncertainty” — that provide local color and root the drama in the modern urban world, whatever the visuals may have signaled.

More importantly, for Abbate and Parker, is the expansion from “exquisite solo expression” to the confrontation of the great duet in Act Two. The story, they write, “confronts some of the most vexed issues surrounding sexuality, not least whether women had the right to choose their own destinies. These were matters that preoccupied people at the time, but had never before been raised so overtly on the operatic stage.”

La Traviata, then, reminds us of the potential for opera to remain relevant, to innovate while staying true to the universal. And the depth and dimension of Verdi’s portrayal of Violetta, who stands apart in the composer’s canon as a heroine of singular complexity, will continue to pose an inexhaustible challenge to singers — and to fascinate audiences as long as opera is performed.

(c) 2014 Thomas May — All rights reserved.

Filed under: essay, San Francisco Opera, Verdi