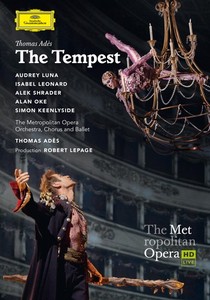

Quite happy to see Tom Adès take the Best Opera Grammy for The Tempest. I had the opportunity to write this essay for the Met when the production staged by Robert Lepage first appeared there:

When The Tempest opened at London’s Royal Opera House in February 2004, the anticipation couldn’t have been more intense. Composer Thomas Adès—only 32 at the time—had already been thrust into the international spotlight in the previous decade and found himself having to live up to recurrent comparisons with his similarly precocious compatriot and predecessor Benjamin Britten. Despite all this pressure, the overwhelming, almost unanimous response to Adès’s second opera seemed to confirm the parallels. “Only time will tell whether the first night of The Tempest in 2004 was a moment to set alongside the first night of Peter Grimes in 1945 in the history of British music,” wrote The Guardian the day after the occasion. “But it felt that way in the theatre.”

Time has proved that the initial verdicts weren’t idle hyperbole. The Tempest belongs to that rare group of contemporary operas whose critical acclaim is matched by the ultimate practical test of stage-worthiness. In fact, The Tempest—still less than a decade old—can already boast an astonishing track record of five different productions: the original Covent Garden staging (which was revived in 2007 and recorded for EMI’s award-winning CD), the American premiere at Santa Fe Opera in 2006, two separate productions in Germany, and now the opera’s premiere at the Met, which promises to be among the highlights of the new season.

Robert Lepage’s staging is a co-production of the Met, Opéra de Québec, and the Vienna Staatsoper and will also feature Adès (pronounced AH-diss) making his company debut as conductor. Reprising his performance as Prospero is baritone Simon Keenlyside, whose combined vocal and physical presence were widely admired as ideally suited to the role he created at the Royal Opera House.

The once-obligatory references to Britten became a kind of shorthand for English critics eager to spell out the high expectations pinned on Adès. In fact, he is an artist whose voice is unmistakably and audaciously original. Many gifted young composers demonstrate an eclectic, anxiety-free facility when it comes to claiming elements from the musical past for their own creative tool kit, but what was especially striking about Adès, while he was still just in his twenties, was the uncanny confidence with which he forged a rich, complex, allusive language with a coherence all its own.

Even more, before the millennium Adès had already found exciting ways to develop his flair for formal, abstract structures, vivid orchestration, and spirited detail while also demonstrating a compelling theatrical instinct. His range was apparent, whether in writing for a large Mahlerian orchestra (the symphonic Asyla, commissioned for the Berlin Philharmonic, for example) or in his first work for the stage, the chamber opera Powder Her Face (1995).

The latter, which used the scandalous story of an aristocrat’s fall from grace to ironically turn the mirror back on a tabloid-saturated culture, also revealed Adès’s extraordinary feel for portraying characters in music. With the far vaster canvas of The Tempest, he progressed to a mature mastery of his art, taming the often volatile energy found in his youthful scores into a sustained, emotionally gripping arc.

Shakespeare’s beloved final romance, remarks Adès, “is famously full of references to music, while the intangibility of some of its characters has always inspired music.” Purcell, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, and Berio are just a few of the many composers who have fallen sway to its spell; even Mozart, near the end of his life, may have contemplated turning The Tempest into an opera. Yet instead of finding himself daunted by the weight of associations bound up with the source material—above all by the sheer power and poetry of Shakespeare’s language—Adès discovered a fresh approach to “translating” the Bard’s vision into opera.

The composer collaborated closely with librettist Meredith Oakes, an Australian-born playwright and poet whose talent for evoking traditional poetic patterns through “a very specific, archaistic style” felt particularly appropriate. Oakes distilled the original verse into pithy, condensed couplets that echo the play’s most famous passages in eminently singable phrases—instead of competing with them. Many of the couplets take the form of half-rhymes or slant-rhymes that acquire an extra charge by being ever so slightly off. The result, Adès says, “is a translation of Shakespeare into modern English, to be all the more faithful and concentrate the drama.”

Yet the three-act opera remains remarkably true to the arc of Shakespeare’s story and the spirit of his characters, while at the same time opening up the creative space necessary for Adès to add the unique perspective of his musical imagination. “I want it to be The Tempest. I want it to be Shakespeare and to bring that vision into the opera house as faithfully as possible,” the composer points out. “We actually started further away from the play than we ended up but found ourselves going back to Shakespeare’s structure much more.” But to achieve such fidelity—as opposed to a pale imitation—Adès and Oakes determined early on that they needed to swerve away from dogged, literal re-creation.

The most striking shift involves the opera’s conception of Prospero, the former Duke of Milan who, in the back story, has been usurped by his brother Antonio and shipwrecked on an island with his young daughter, Miranda. Prospero’s desire for vengeance is more pointed in the opera, as is his related assertion of control over the island’s indigenous creatures—Ariel and Caliban—and over Miranda’s emerging emotional autonomy as she falls in love with Ferdinand, his enemy’s son.

The libretto provided Adès with clearer “musical emotions” that motivate the dynamics of enslavement and liberation in the story as well as the transforming power of love and compassion. The real turning point, observes the composer, comes when Ariel tells Prospero that the suffering he has caused his enemies to endure would soften Ariel’s own heart if he were human. “And it’s the moment when Prospero realizes he’s gone too far and has to stop.”

Lepage, familiar to Met audiences for his stagings of Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust and Wagner’s Ring cycle, praises the opera for capturing the “magic” of what is often considered the playwright’s final artistic testament. Not surprisingly for this wizard of theatrical illusion, the figure of Prospero has long fascinated Lepage, who has directed numerous productions of Shakespeare’s play. Each time he returns to it, he uncovers new insights. For his own concept of the opera, Lepage has expanded its aura of magic into a metaphor for artistic performance itself, envisioning Prospero as an 18th-century impresario of La Scala, the opera house in Milan, which he has recreated on the island of his banishment as a reminder of home.

“In those days, La Scala was a very magical place to set operas because it had all of the new state-of-the-art machinery,” Lepage explains. “The beach where everybody is marooned is actually a stage that’s been planted there and constructed by Prospero.” Lepage adds that each of the three acts presents a different perspective—from the stage itself, from the auditorium, and what goes on behind and off stage—to encompass this “opera-within-an-opera house.”

Members of his creative team will be making their Met debuts: Jasmine Catudal designed the sets, and the costumes are by Kym Barrett (known for her collaborations with Baz Luhrmann and her work on The Matrix films). The overall look will marry a sense of the island’s “native, aboriginal culture” with the Italian Baroque sensibility imported by the European interlopers.

Lepage’s mastery of both traditional stagecraft and its most up-to-date technological forms provides an ideal complement to the composer’s unique fusion of a classic play with a contemporary vision of opera. In his musical characterizations of the five leads, for example, Adès developed wonderfully effective alternatives to the vocal type casting that might have tempted a less-imaginative composer. While Ariel, a male character played by a soprano, sings in a stratospheric tessitura (frequently perching on Ds, Es, and Fs above high C, even reaching to G), “this isn’t a way of expressing high emotion and shouldn’t feel like the top of the singer’s range. That’s where she lives.”

Ariel is an elemental force of nature who—in another alteration of the original source—sings the final airborne phrase and becomes the wind again. Her island counterpart, the “monster” Caliban, is depicted not as a “lumpen, earthy brute” with a bass voice but is a lyrical tenor. “He’s often described in the play as being like an eel or a fish, and I suddenly thought he could be more like one of those exotic, wonderful voices from the East, with a weird elegance. And of course he is an aristocrat, not only in his own mind,” says Adès, who gives Caliban one of the most radiantly beautiful passages in the score: his aria reassuring the shipwrecked newcomers not to fear the island’s “noises.”

As for Prospero, the composer created a fully dimensional baritone role (with shades of Verdi’s and Wagner’s authoritarian father figures) who nevertheless defies the stereotype of the wise old sage. Adès was especially inspired by crafting the role for Keenlyside. “Simon’s a terrifically physical performer who projects youth. In a way, it’s that characterization, as much as the extraordinary voice, that was on my mind. I don’t think of Prospero as an old man. This is the only play of Shakespeare which observes the classical unities of happening in one place, in one day. When Prospero meditates on the evanescence of life, my feeling is actually it’s not that he does that every day and has been doing it for years and he’s an old bore. It’s that he’s just realizing it at that exact moment. That’s the first time he’s thought this.”

While Adès writes for the voice with great character, his score is also distinguished by its symphonic intricacy and architecture. This quality provides the opera with a richly satisfying cohesion and unity. Adès achieves this not through conventional leitmotif technique but by expertly manipulating his uniquely evocative harmonic language. He explains: “The music has its own internal logic of relationships; it doesn’t just do what it wants to do because the characters suddenly decide to go somewhere. It’s a tissue that’s woven in, so that everything is related in the music, and all the elements create a view of the world that’s whole, a sphere.”

(c) 2012 Thomas May – All rights reserved.

Filed under: Metropolitan Opera, new music, opera, Shakespeare