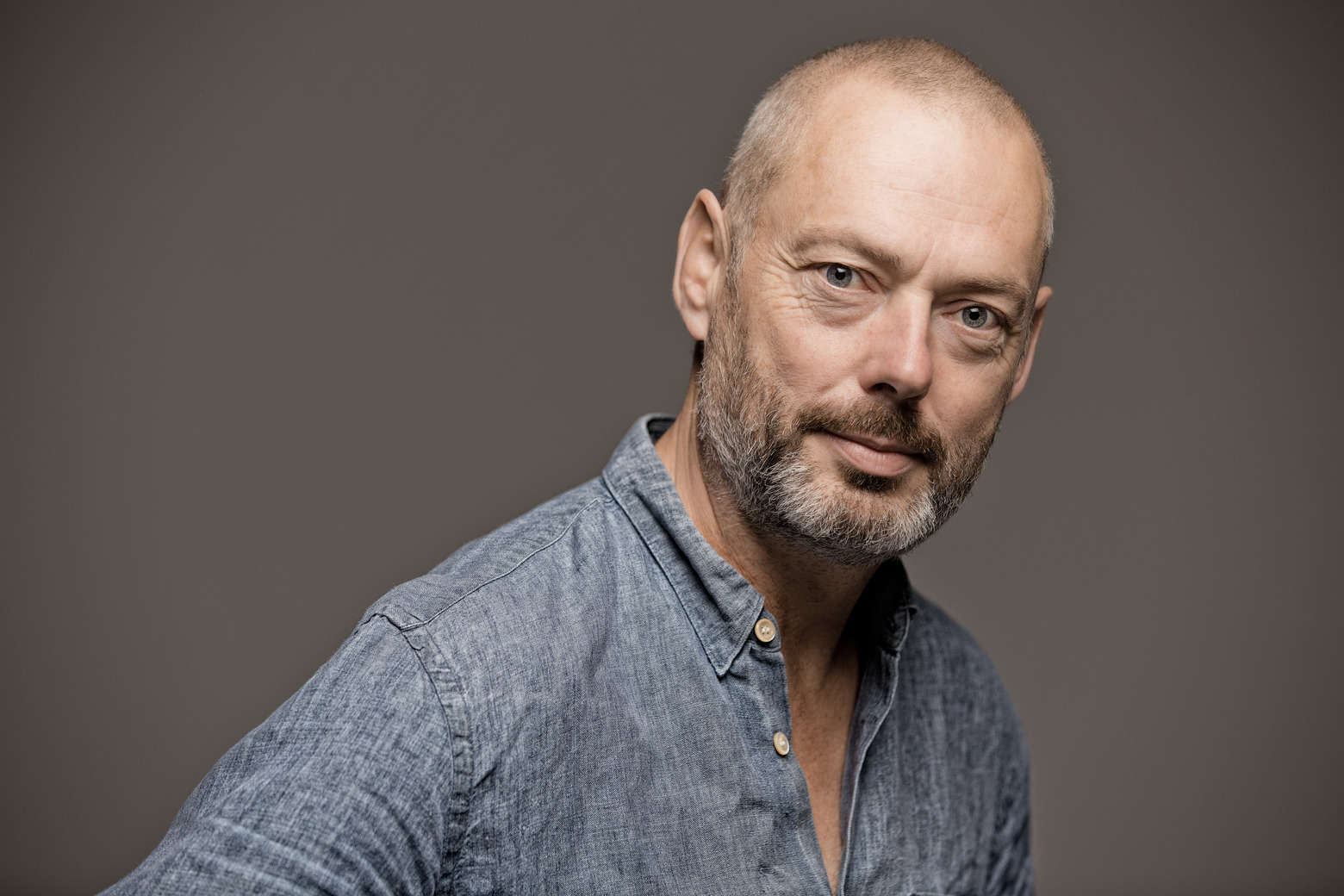

Kevin Lin as Hamlet; photo (c) Kyler Martin for The Horse in Motion

Hamlet is usually encountered as an object of reverent study or, in performance, a vessel of virtuosity. But in its recent staging at an old Seattle mansion, The Horse in Motion found a way to turn the play back into a visceral theatrical experience — one full of discovery for bardolaters and newcomers alike.

In lieu of a traditional theater, the action was set in (and around) the Stimson-Green Mansion, a meticulously preserved 1901 home with an English Tudor Revival exterior and a wonderfully eccentric, all-over-the-place interior, located on Seattle’s First Hill.

But the novelty of presenting Hamlet as a site-specific event turned out to be just one facet of this adventurous company’s innovative take. Brooklyn-based director Julia Sears double cast Hamlet‘s major roles among a team of eleven actors, thus creating two simultaneous productions that unfolded in different rooms of the mansion.

The audience — limited to about 40 people for each performance — was correspondingly split in two and given a cast list designed as an invitation either to the wedding of Claudius and Gertrude or to the funeral of Hamlet Senior. In various key scenes, the two casts converged in the same space, so that, for example, we saw twin Hamlets confronting the same situation — as if these parallel universes had suddenly intersected.

At these face-offs, the double Hamlets and colleagues divvied up their lines or enacted them simultaneously. Sometimes the actors from the other cast were close enough to be audible, the slightly unsynchronized delivery intensifying a sense of patterns being eerily repeated — like a familiar ghost story retold, with just enough of a sick twist to add a new frisson.

Mario Orallo-Molinaro, Katherine Bicknell, and Kevin Lin; photo (c) Kyler Martin for The Horse in Motion

Virtuosity there was indeed, but a kind of virtuosity even more demanding than usual. For instance, Kevin Lin played Hamlet for the group to which I was assigned (the wedding party) during the second-to-last performance (28 April), homing in on the prince’s sense of desperate frustration to powerful effect. But in addition to this monumental assignment, he had to morph into Laertes for the “funeral” production and calibrate his interpretation to that of the other Hamlet, the commandingly eloquent Jocelyn Maher (who, in turn, was our Laertes).

Specific angles in the wedding cast — the intensity of the sexual bond between Claudius (Ben Phillips) and Gertrude (Tatiana Pavela) — made me curious about the parallel chemistry in the funeral cast’s scheming royal pair. Gender-blurring assignments also added a fascinating dimension to the experience. Along with the male-and-female Hamlets and Laerteses, both Hannah Ruwe and Nic Morden were double Ophelias (as well as Horatios). During the “mash-up” scenes, we saw both manifestations of Hamlet and Ophelia interacting with each other. Polonius, meanwhile, was played as a society matron by Laura Steele in both casts.

This may sound like a merely clever concept, but in performance it was riveting from start to finish, reinforcing what is at stake in Hamlet with unforgettable theatrical power. “Who’s there?” — the play’s first line, delivered urgently on a chilly, damp lawn next to the mansion — acquired fresh implications.

l to r: Jocelyn Maher (Hamlet), Mario Orallo-Molinaro (Guildenstern), Ben Phillips (Francisco), Ian Bond (Claudius), Ophelia (Nic Morden), and Hannah Ruwe (Horatio); photo (c) Kyler Martin for The Horse in Motion

Jenn Oaster’s early-20th-century smart-set costumes, enhanced by Alex Potter’s period music sound design, evoked associations from the era when the Stimson-Green Mansion was built, of ghosts from its particular past. On one level, this suggested Hamlet’s tragedy playing out in a particular context of privilege, his madness presenting as fragmentation.

But Sears’s vision probed well beyond the psychological realism that has become the default setting of too much contemporary theater. I especially relished the surreal effects of the doubling, as well as the ironic humor of defamiliarizing such iconic scenes by means of another kind of familiarity — i.e., an imagined upper class family life in this setting. (Speaking of humor. Ian Bond’s cliché-free, inventive performance as the Gravedigger in the final act was itself worth the price of admission.)

Sears and her design team made imaginative use of the variety of spaces available on the premises. Instead of a fourth wall to break, the setting itself became a protagonist, offering new elements to explore with each gently orchestrated redirection of the audience to a different room: a raging fire in the hearth, a trip up creaking stairs for the genuinely intimate bedchamber scene, a spacious ballroom where the overwrought, speedy finale of death plays out after so much anticipation. (One quibble: the amplification device for the cloaked Hamlet’s Ghost — curiously, not credited in the program listing — distorted too many words in that crucial scene.)

I asked a friend who was also part of the wedding party for his impressions of this nontraditional performance setting. He told me that the experience of “moving along with the cast, and in such close quarters, brought us closer to the play than we ordinarily might have been.”

I’ve never actually felt nervous before during Hamlet and Laertes’ final fencing match. This time, I was viscerally aware of the nuances of the fight choreography as the rapiers clashed inches away. The only drawback was that the logistics limited the audience size, so that local theater lovers who didn’t plan ahead missed out on this remarkable experience.

As the dead bodies, doubles included, lay strewn about, not even Fortinbras (the excellent Mario Orallo-Molinaro) could set things right. Sears’s final touch removed the precious sliver of optimism the Norwegian crown prince represents, making him another victim of the sad state of this world.

–Review (c) 2018 Thomas May. All rights reserved.

Filed under: Horse in Motion, review, Shakespeare