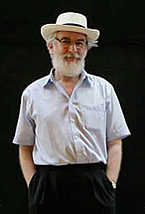

Rosa Joshi

This is a fuller version of my profile of the Seattle-based director Rosa Joshi for Crosscut.com. Joshi and her team at Seattle Shakespeare Company have staged Richard II, a play that’s been in the spotlight thanks to the BBC’s Hollow Crown series but that — at least in the U.S. — remains a relative rarity.

“I don’t choose easy plays!” admits Rosa Joshi. She’s explaining her selection of Richard II as the vehicle for her directorial debut with Seattle Shakespeare Company.

The match between Joshi and Seattle Shakes is long overdue, given what she has brought to the Bard’s twist on “sad stories of the death of kings.” For my money, her Richard II ranks among the finest of the company’s recent productions, achieving a delicate balance of clarity and forceful poetic imagination.

“Shakespeare is my greatest love to direct,” says Joshi, who has been on the fine arts faculty at Seattle University since 2000.

“There are no small choices in Shakespeare. He makes you go to the extremities of emotion and experience, from the heights of joy to the depths of despair. That to me is infinitely challenging.”

Extreme situations frame Richard II, which traces the downfall of its titular king. Ill-suited to the throne, the impolitic Richard is forced to hand the crown over to his cousin-made-rival, Henry Bolingbroke, before being imprisoned and assassinated. His dramatic reversal of fortune has its counterpart in Henry’s equally dramatic ascent.

Richard (George Mount) surrenders his crown to Henry Bolingbroke (David Foubert); photo by John Ulman

Over the past decade, Joshi has made a splash in Seattle with her all-women versions of Shakespeare. In 2006 she co-founded upstart crow, a local collective devoted to producing classic theater with exclusively female casts. Their inaugural production took on the Bard’s King John; their second effort followed in 2012 with the ultra-violent Titus Andronicus.

A central aim of upstart crow has been “to create opportunities for women to participate in the Western classical canon for which they share a passion – in a way they don’t get to do in more conventional arenas.”

“Any time you have one gender onstage it makes you look at gender differently,” Joshi says. “I’m not so much prescriptive about what it means, but think of it as an experiment in how the audience relates to the work. For some people, the gender simply goes away, and some people really notice it. There isn’t just one experience I’m trying to make the audience have.”

Joshi is well-aware of the seeming paradox that with the conventionally cast Richard II at Seattle Shakes, she’s chosen a play featuring a predominantly male cast (with just two actresses). In fact, she points out, upstart crow has also gravitated toward heavily male plays.

“With Richard, there is a way of looking at him as a character who has a certain female energy in a male world,” Joshi explains. As he loses the confidence of his subjects, Richard becomes increasingly marginalized. The actual women in the play, meanwhile, “are the only ones who hold on to family while the others are torn by loyalty to the state.”

Richard (George Mount) and his Queen (Brenda Joyner); photo by John Ulman

In a similar vein, Joshi expresses puzzlement over another question she says is inevitably posed: “Why do you, as a woman of color, insist on doing this work by Dead White Males? Whenever I’m asked that, I point out that these plays are just as much my heritage, too.”

Joshi, who grew up in England and Kuwait, initially thought she was destined to become a doctor like her father. Still, she decided to keep her options open by studying in the United States and pursuing her love of theater on the side as a double major.

The turning point that made her decide to choose theater over medicine came when she was given the chance to direct during a semester abroad in London. Naturally, it was a thorny piece: Harold Pinter’s one-act “The Lover.”

After internships at the Williamstown Theatre Festival and Juilliard in New York, Joshi headed to Yale Drama School (during the Stanley Wojewodski era). Her classmates included Paul Giamatti, Liev Schreiber and the indie director Tom McCarthy. “I learned so much just from being around my peers,” she recalls.

Joshi relocated to Seattle during the 1990s, when the fringe theater scene was exploding. Legendary local director John Kazanjian of New City Theater, she says, became a key mentor. Kazanjian gave her the opportunity to produce her own shows — including her Seattle debut, a “Twelfth Night” staged on the steps of Capitol Hill’s Richard Hugo House.

“I think Seattle is a great place where emerging artists can sink their teeth into work. But it’s harder to sustain mid- and late-career artists.” Still, Joshi sees a positive development in the resurgence of adventurous theater in recent years from groups like New Century Theatre, azeotrope, Washington Ensemble Theatre, and Strawberry Workshop.

“A lot of these are companies started by artists who realize they need to self-produce: artists who have a shared mission and the expertise to produce their work, which is empowering. One of the things we try to promote here at SU to my students is the idea that they need to be nimble and able to do more than one thing.”

Joshi herself had taken that advice to heart during her early years in Seattle by self-producing. A stint as artistic director at the Northwest Asian American Theater got her involved in collaborations between Asian-American and Asian artists.

Since taking up her position at Seattle University, Joshi has guest directed at several Seattle theaters. She seems especially at home with Seattle Shakespeare, where she coaxes a poetically nuanced performance of the doomed Richard from George Mount, the company’s artistic director.

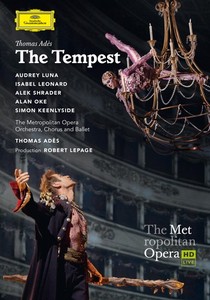

Cast of Richard II; photo by John Ulman

The complexity of Richard II, along with its confusing back story, poses daunting challenges for any director and cast. But Joshi and her actors bring a red-hot focus to what’s at stake for the two sides, and the story plays out with riveting dramatic rhythm.

It is Shakespeare’s ability to convey all of this through elaborately poetic language that particularly enthralls Joshi. Richard II is his only play written entirely in verse (even a gardener and his assistant carry on in lofty iambic pentameter).

“He’s able to use language to convey the inner workings of character and to externalize the souls and emotions of these characters,” Joshi explains. “At time we might feel the language is excessive: and that’s exactly the language we need in order to understand what’s going on with Richard.”

“I know lots of directors work from a very visual world, but I consider myself very text-driven.” Which hardly means Joshi’s work can’t be strongly visual — her production’s most indelible image reverses the moveable throne that dominates the minimalist set so that, in the prison scene, it becomes a looming gravestone — but she emphasizes that she wants such visual ideas to “emerge from the text. And what richer playground is there than Shakespeare, where the text delivers and encapsulates so much.”

Joshi is also intrigued by the ways in which Shakespeare blends the genres of history and tragedy in Richard II. And though it’s one of his less frequently staged plays, Richard II strikes a relevant chord because of the very modern crisis Richard faces, even within the play’s medieval setting.

Joshi points to Richard’s most self-reflective moments in the pivotal Pomfret Castle prison scene. “Take his lines: ‘but whate’er I be,/Nor I nor any man that but man is/With nothing shall be pleased, till he be eased/With being nothing.’ The density of meaning in that has always struck me as something that could be out of Samuel Beckett.”

“The existential journey that Richard goes through is something I think contemporary audiences can relate to in terms of how we define ourselves in the world. Richard has to grapple with who he is when he’s no longer king.”

“How does he cope with the absence of that identity? How does Henry edit his identity in order to become a leader? And how much are both shaped by who they are versus the people they have around them? Do we get the leaders we deserve?”

Richard in Pomfret prison; photo by John Ulman

In fact, Richard II appears to have become a hot theatrical topic of late. Recent broadcasts by the BBC of The Hollow Crown series (the cycle of four history plays that begins with Richard II) has brought the melancholy Richard into the spotlight – as has a much-touted Royal Shakespeare Company production starring David Tennant as the deposed king, which was widely disseminated via HD cinemacast.

For Joshi, it’s no surprise that Richard II is suddenly brimming with contemporary relevance. “The history plays seem to come up more and more in part because we live in a politically cynical age. These are plays that focus on what people do for power and ambition. The first week of rehearsals, one of the news stories was of how Kim Jong-un had his uncle executed to consolidate his power.”

Yet in this case, Joshi has seen no need to “modernize” the setting in order to emphasize its relevance. “I’m always interested in the artificiality of theater. What does theater do that film doesn’t do?”

“We don’t compete with the kind of verisimilitude that you get in film because theater demands that the audience’s imagination be engaged to complete the experience. It is this pact we go into – audience and actors and designers – to create this world together through this act of imagination.”

(c) 2014 Thomas May. All rights reserved.

Filed under: directors, Shakespeare