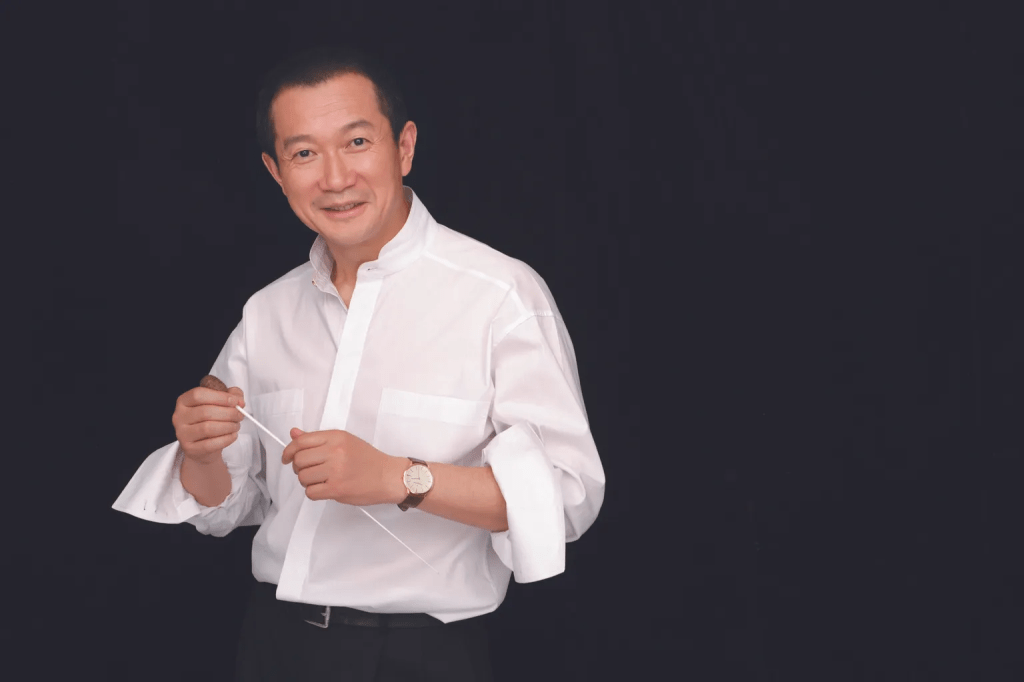

A concert built around the artistry of composer, conductor, and cultural connector Tan Dun offers no shortage of conceptual fascination. This week’s concerts mark his turn to the Seattle Symphony podium after a memorable debut here two and a half years ago, when he led his monumental Buddha Passion.

Raised in a remote village in China’s Hunan province and shaped equally by Western classical forms and ancient Chinese traditions, Tan – who since 1986 has been based in the US – brings a theatrical imagination and a deep sense of ritual to the concert stage. He framed last night’s program with a pair of short but intensely colorful works by two early 20th-century composers he admires, serving as explosive preludes to two large-scale pieces from his own catalog.

A vivid reading of Manuel de Falla’s Ritual Fire Dance, from his 1915 ballet El amor brujo, crackled with rhythmic energy and flared with instrumental color, setting one element against another as water came into protracted focus in the ensuing Concerto for Water Percussion and Orchestra, composed by Tan in 1998 and dedicated to Tōru Takemitsu.

Tan draws out music’s ritual origins in intriguing ways. Percussionist Yuri Yamashita not only performed the solo part but dominated much of the piece with an almost shamanistic stage presence – from the way she mindfully released droplets from her fingers to the immersive sound world she conjured using bowls of wood or glass, as well as gongs dipped mesmerically into one of two large water bowls over which she presided.

At some moments she even softly vocalized, as if engaged in a conjuring. Enhancing the theatrical experience were three video screens suspended above the orchestra –- one large at center and two smaller flanking it – which projected close-up footage of the bowls and the rippling water, inviting the audience into the tactile, elemental, organic world of the piece.

The orchestra functioned as a kind of elemental chorus, not so much a counterpart as a kaleidoscopic resonator. Specific voices occasionally emerged from the fabric – most memorably in a luminous duet between Yamashita and principal cellist Efe Baltacıgil, whose tone seemed to bloom out of the water’s surface. A long, improvisatory cadenza captivated with its focus on the physicality of sound.

Still, the Water Concerto’s meditative pacing and episodic structure began to feel diffuse over the span of the piece – though whether this observation reflects a Western bias about form or a real imbalance in proportions is a fair question. In any case, this was a welcome opportunity to hear the work in live performance.

After intermission came a brisk, glittering account of Stravinsky’s Feu d’artifice (Fireworks), a four-minute burst of orchestral color dating from a little before the young Russian’s leap to international fame with The Firebird.

To this taste, the highlight of the program was Nu Shu: The Secret Songs of Women – a 13-part multimedia concerto that unfolded with greater emotional clarity and formal cohesion than the Water Concerto. Nu Shu originated as a commission for a harp concerto from the Philadelphia Orchestra but, inspired by Tan’s immersive research into a little-known linguistic and social tradition from his native Hunan Province, grew into a sui generis fusion of concerto, orchestral narrative, and ethnomusicological-sociological documentary.

The “secret songs” in question have to do with the vanishing Nüshu tradition — a secret, invented language once used by women in rural Hunan to communicate among themselves in calligraphy and through chanting and song. Tan painstakingly researched the small community of remaining Nüshu speakers, capturing their voices and stories in multiple videos.

Nu Shu unfolds in 13 short video portraits created by the composer and his team – shown on the three screens above the stage – each anchored in the landscapes of the women’s daily lives and their stories of isolation and solidarity, which are shared from generation to generation.

For Tan, the harp represents “the most feminine of instruments,” writes Esteban Meneses in his excellent program note, and serves as “an intermediary between what the composer imagines as the future – the Western orchestra – and the past, represented by the microfilms.”

Xavier de Maistre was the eloquent soloist, playing a kind of bard who mediates these stories and showing remarkable dynamic and expressive range. Tan likewise assigns a crucial narrative role to the orchestra, which acted as a bridge translating memory into something shared and immediate.

Repeat performance on Friday, May 16, at 8 pm.

(c)2025 Thomas May

Filed under: review, Seattle Symphony, Tan Dun, art, classical-music, jazz, music